This article is based on an article in the Reader’s Digest, June 1957 issue, written by an eyewitness, Frederic Sondern Jr.

Port-au-Prince, the capital of the Republic of Haiti, located on an island it shares with the Dominican Republic, is an active and bustling city. But one day in December 1956 no one could be seen on the street; It looked like a ghost town. Businesses and stores were closed, docks deserted, fishing boats tied up. Its inhabitants had gone on strike against Paul Eugene Magloire, the ruler of Haiti.

Port-au-Prince, the capital of Haiti

Paul Eugene Magloire came to power on December 6, 1950. During his first years in government, he did not do badly: tourism increased, the price of coffee (his main export product) rose on the world market, he built roads and schools. But in 1954 Hurricane Hazel devastated the island and Magloire’s popularity plummeted.

Hurricane Hazel, October 15, 1954

The Haitian constitution established that the presidential term lasted six years and that the president could not be re-elected. So it is, on December 6, 1956, Magloire had to hand over command. The Supreme Court was then to assume the government until a new president was elected in April 1957. But as has happened and is happening today in many countries (which shows that this is nothing new), Magloire wanted to continue in the power to further enrich himself and was willing to use violence to achieve it. It is thus that he prepared a farce:

On Wednesday, December 5, several bombs exploded in various places in the capital; following the plan, the police chief muzzled the press and radio and spread the rumor that disgruntled businessmen led by wealthy landowner and senator Louis Déjoie (Magloire’s harshest critic and main contender for his successor ) and supported by the US ambassador, had placed bombs all over the city as the first stage of a plot to seize power and establish a dictatorship.

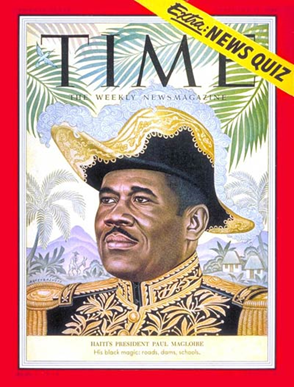

Paul Magloire

The next day, Magloire, dressed in one of his resplendent uniforms, solemnly handed over command at the palace. But immediately the army chief of staff radioed the nation declaring that the homeland was in danger, that a plot had been exposed, and that the Supreme Court refused to take over the government. Therefore, he announced that the army had begged General Magloire to agree to assume the functions of provisional president and commander-in-chief for an indefinite period (ie, for life).

With tears in his eyes, Magloire replied that he had to accept this burden against his will, as it was his duty to the country. This ruse caused stupefaction among the population, but then Magloire’s first move as provisional president was to suspend the constitution and declare a state of siege. At the same time, the police chief sent patrol trucks armed with machine guns throughout the city, to silence the slightest attempt to protest. Soon after, the trucks arrived at the central jail, loaded with people, including teachers, writers, businessmen, lawyers, and also Senator Louis Déjoie.

That evening, in the massive Quinta de Magloire, a jubilant celebration took place, with pro-government guests fawning and wishing a long life to the “president”, who was beaming and feeling very secure in power.

Celebration in Palace

But there was a flaw in the plan. After six years in government, Magliore had lost contact with the people of the town and forgot that this town had a peculiar weapon: the télédiol, a kind of “oral telegraph”, very effective, by means of which the details of the coup state perpetrated by Magliore, were on the lips of almost all the inhabitants of Haiti 24 hours after it happened. It was a unique system of collecting and transmitting news, so efficient that on Saturday afternoon, the entire population of Port-au-Prince and almost the entire population of the country knew that there would be a general strike on Monday.

On Monday, December 10, the schoolchildren missed their classes, the judges did not come to court, the food market was empty and almost all the shops and industries were closed and those that were open were preparing to join the strike. Magloire was furious but the police chief told him that so many people could not be arrested. At this Magloire led a caravan of cars heading for the main street and stopped before the most important store in the city, which was already preparing to close its doors. At machine gun point, he forced the workers to continue their work. He did the same with the other stores.

Empty streets due to strike

But as soon as the troops left, the businesses closed again. Out of his mind, on Tuesday afternoon Magloire had 32 of the main merchants brought to the Palace, threatening them and their families if they did not open their shops the next day. In addition, he made them sign a paper stating that the strike was organized by US firms, acting in conjunction with the opposition to his government. All 32 signed.

The official radio announced triumphantly that the strike was over and that the next day everyone would go to work. But the population thought otherwise. The télédiol already knew the details of the scene developed in the Palace. On Wednesday Port-au-Prince was still paralyzed and the 32 signatories of the document had disappeared. Magloire’s first impulse was to continue using force, but the police chief told him that some young officers were showing signs of insubordination. Seeing that nothing would be achieved with threats, he decided to change tactics.

On Wednesday afternoon Magloire appeared before the presidents of the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies and before the judges of the Supreme Court and handed over command to the president of the Court, Joseph Nemours, who immediately ordered the release of all political prisoners. The population took to the streets to celebrate; there was joy everywhere and people hugged each other. But suddenly the celebration stopped. The télédiol communicated that Magloire was still commander-in-chief of the army and therefore dictator. He had to leave the country to secure Haiti’s freedom.

On Thursday the streets of the capital were the same as they were on Monday: empty and silent. In the afternoon a group of officers went to see Magloire to ask him to leave the country. He did not take the officials’ request seriously but they replied that they would withdraw the Palace guard and then he would be at the mercy of the crowd, who were not exactly happy. Resigned, Magloire agreed to go. An hour later he, his family and a large number of trunks were at the airport ready to leave Haiti. The télédiol had triumphed.

On Friday morning everything was back to normal and Port-au-Prince was once again the lively and bustling capital of the Caribbean. The article in the magazine Selecciones ends with a few words that a Haitian said to Mr. Sondern (who was amazed that a bloodless revolution had succeeded):

- We just don’t like dictators.

Unfortunately for Haiti, on October 22, 1957, François Duvalier assumed the presidency of the country, who would become one of the bloodiest dictators in the Caribbean.

Of humble origin, Duvalier managed to study medicine and, already as a doctor, had a prominent role in the fight against the epidemics of typhus and malaria that plagued the island, gaining popularity; he was also one of the main opponents of Mangloire.

François Duvalier

But it was not long before he began to exercise a brutal and repressive government, imprisoning or murdering his detractors. But how did Duvalier defeat the télédiol?

First, he organized a paramilitary group of volunteers who supported his regime, known as the Tonton Macuotes. According to estimates, the number of these volunteers was between 25,000 and 50,000. Mixed among the population made it difficult, if not impossible, for the télédiol to prosper. It was a ruthless group that only reported to Duvalier and financed itself with the proceeds of his crimes. It is estimated that, in its almost 30 years of existence (with François Duvalier, from 1958 until his death in 1971, and with his son Jean-Claude, from that year until 1986) they murdered some 60,000 Haitians, some publicly and many them with previous torture.

Badge of the Tonton Macoutes

Secondly, Duvalier knew perfectly well voodoo, the predominant religion among the least favored of the population, who were, for the most part, those who led him to victory in the 1957 elections. He became a powerful priest and was considered the reincarnation of Baron Samedi, one of the spirits of Haitian voodoo.

Ritual elements used in the practice of Voodoo

It was said of François Duvalier: “Torture, prison and executions”, is what the doctor prescribed.

REFERENCES: Selections magazine and internet.

Labadee, Haiti beach

Virtual Realities Collide: Embark on a Digital Odyssey of Discovery! Lucky Cola

From pixels to glory – witness the evolution of your gaming legacy. Lodibet

Unleash Your Inner Hero: Conquer Challenges, Collect Triumphs! Lucky cola